I photographed Annela as thunder raged around her house in Estonia. At one point the storm even cut us off completely. Annela’s first COP was in 2009, where she attended as part of the Estonian government delegation. This year she is the EU’s lead negotiator in Response Measures. “We always negotiate the actual draft decision texts in English, whether formally or informally. But the language negotiators use is very specific and certain words hold a lot more weight than they might otherwise in normal use. We do not record the negotiations outside plenaries, and we do not name specific parties and don’t attribute what they say. When I am negotiating I like to have my team next to me and behind me. So that they have my back. It’s really difficult to negotiate alone in front of my laptop. We use WhatsApp with our team, but it’s not the same. The different time zones also makes international negotiations on-line difficult. At the in-person meetings, we may have jet lag, but at least we are all in the same time zone. It’s really important to have long term negotiators because they remind us what has already been thrashed out in the past. I am trying to get off-ground a network of senior women negotiators. It is important to have this kind of support system for women. They are sometimes reluctant to take leading roles because of their other responsibilities. Mirtel my cat, has been supporting me during recent negotiations - sleeping behind my computer screen during early morning negotiations.”

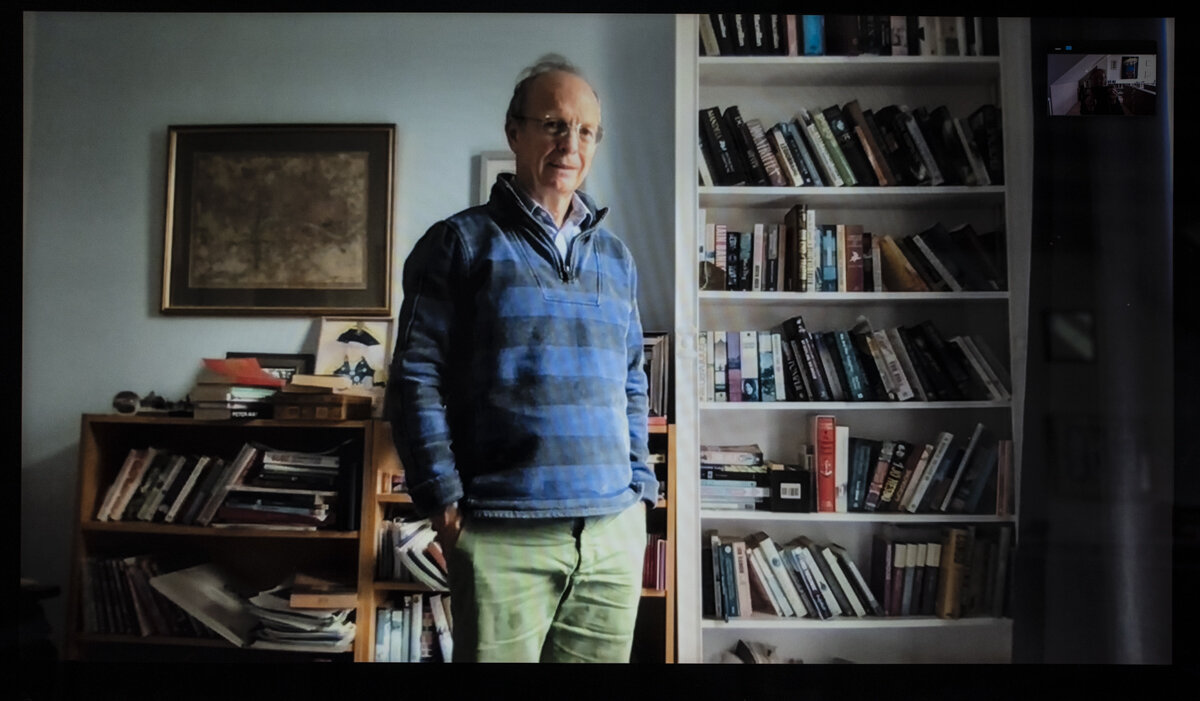

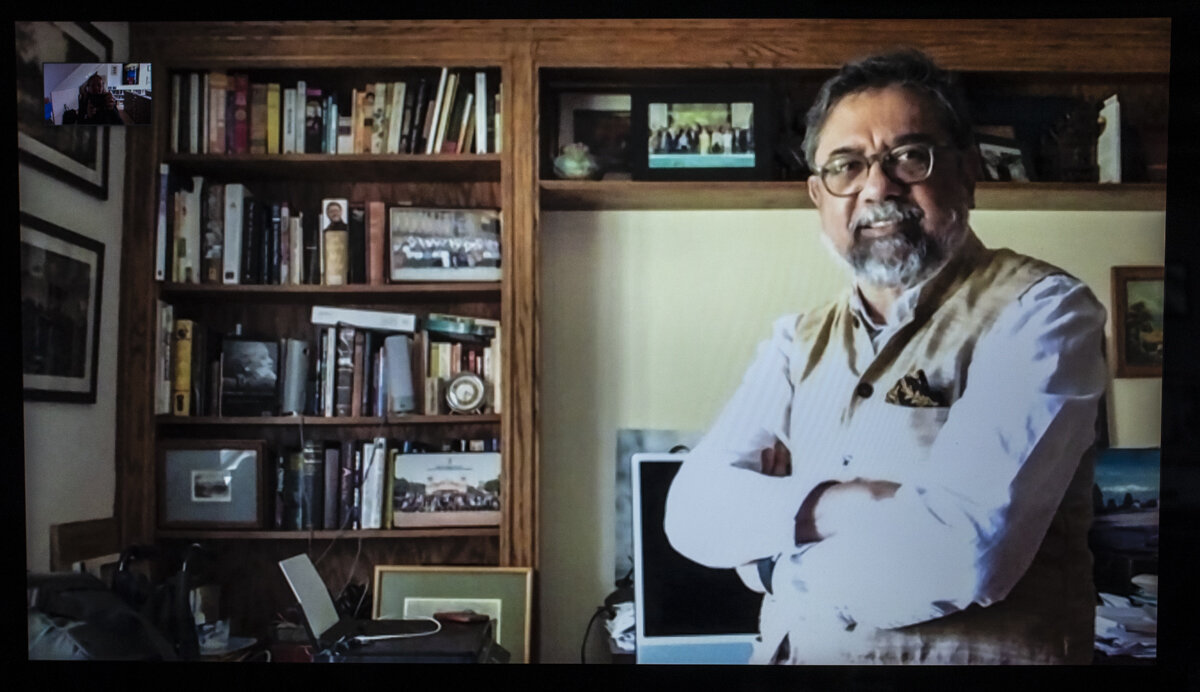

Manjeev represented India at the COP negotiations between 2005 and 2009. “My first meeting was in Montreal and it was extremely cold outside. Not something I had been used to. It was a steep learning curve when I first became involved in the negotiations. I’d been in the foreign service before but I entered as a mid-level negotiator. At the time the US were very concerned about the developing countries not having to do enough. We wanted to developed countries to lead, while we did what we could. In Bali it was similar, the US were putting pressure on India to take more responsibility, but the Indians wanted differentiated responsibility. At that time it was still difficult to communicate with minister back home. We didn’t have smart phones and so sometimes by the time you had connected with your people the discussions had already moved on. The interesting thing about the UN methodology is that there has to be consensus. These COPs were the most defining negotiations of a generation. Of all the things we negotiate, climate change is the one where international cooperation is essential. The negotiations were among the most exhilarating things I have been involved in both intellectually and in terms of what I stand for. Everyone has a personal stake in it.”

After three video meetings to make this portrait with Bo Kjellen, veteran climate negotiator, I can testify that he does not give up easily. We battled with limited bandwidth, computing power and a broken webcam until finally Bo’s face appeared before me. I was so delighted to make a brief connection that I can only look at this image and smile. I am sure this tenacity is why Bo was such a successful negotiator. He was involved in climate discussions from the early 1990s. Bo was Sweden’s chief negotiator at COP1, where he led international negotiations along with some promising colleagues: “The discussions were difficult but eventually we agreed the Berlin Protocol. The German environment minister, Angela Merkel, was very helpful.” At the decisive COP3, Bo was instrumental in finding agreement between the EU, the US and the Group of 77 developing countries. Their wording was accepted at the final hour and contributed to the landmark Kyoto Protocol that is still in place today. When George W Bush entered the White House and threatened to derail the negotiations, it was Bo and his Swedish colleagues, in the capacity of the EU presidency, who convinced the Americans to remain passive. Bo will follow COP26 from his home in Uppsala: “I’m sure the Brits will make the best out of Glasgow. It’s possible that after recent events there will be support for something big.”

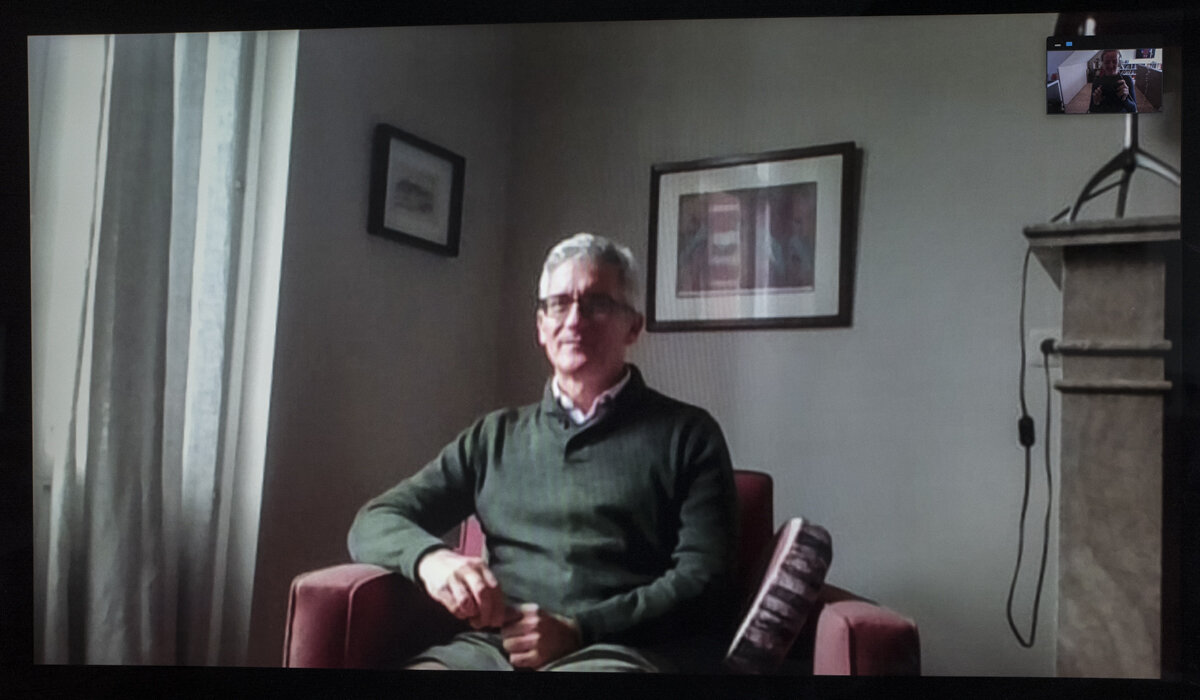

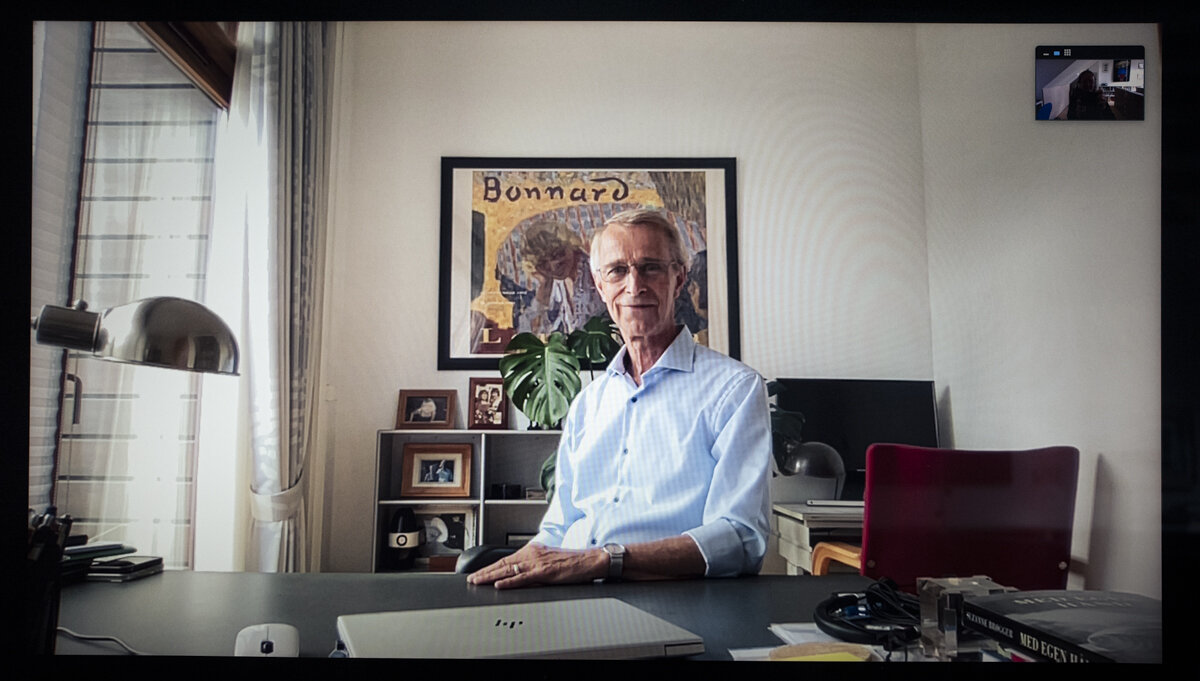

Frode has attended 8 COPs since 2002. He will attend COP26 and is primarily working on the adaptation agenda, helping more vulnerable nations to cope with the challenges that climate change brings. “Cities like Paris, Kyoto, Bali, Copenhagen, are no longer just a place on a map to me. Their names have taken on a much greater meaning as landmarks in the climate change journey. Over that time, other negotiators have become like family. You get to know each other so well during the intense, around the clock, meetings. The relationships are very special. In addition, the world has changed so much since the negotiations started. Back then we had a simplistic distinction between rich and poor countries. Now the world is much more diverse and the differences are much more nuanced. Some countries find it hard to move their negotiating position on, even though their economies have become much stronger. ”

Marco has been passionate about climate change since the early 1980s when, as a teenager, he used to insist on walking everywhere to avoid emissions and as a kind of protest. His first COP was in 2003 in Milan and he has been to several COPs since then, including Madrid in 2019. “Negotiating on climate is a mixture of passion and patience. The UN machinery is huge, and on top of that there are all the sovereign member states, but there is no alternative but to try and bring everyone along through negotiation. Right now I feel hopeful because key players like the EU, China, Brazil and the US are committed to ambitious goals, notably climate neutrality by 2050 or 2060. A lot needs to be done before we get there, but this level of ambition unprecedented”

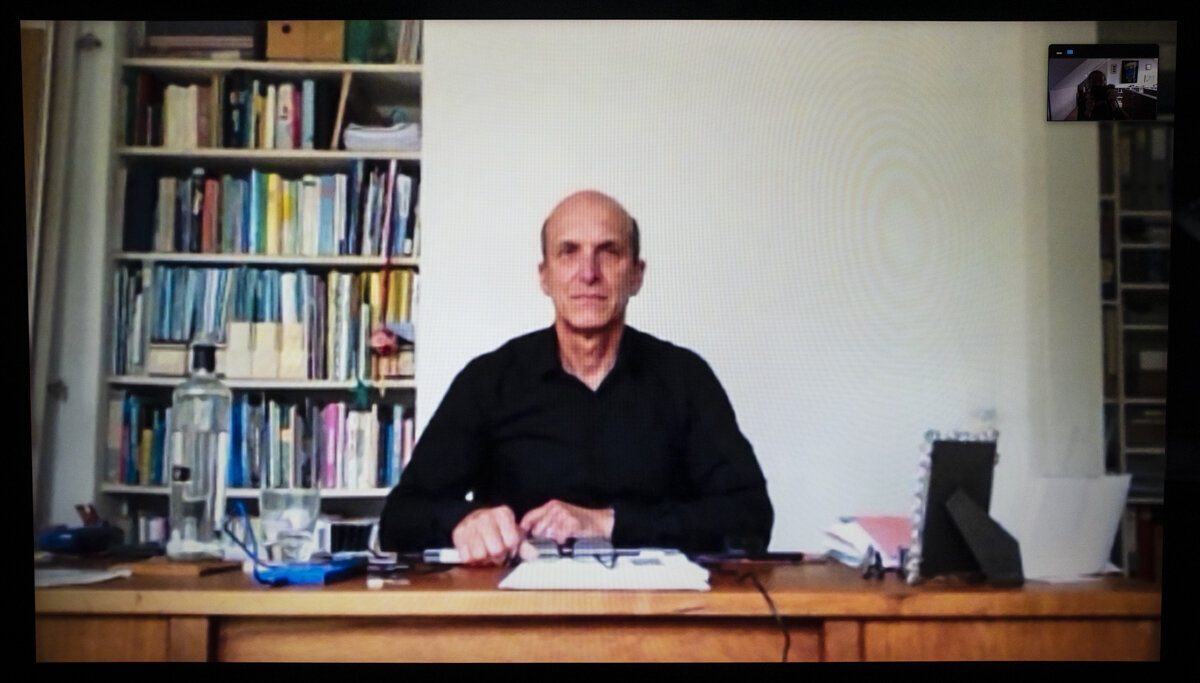

Stefano is from Switzerland and has been involved in climate negotiations since 1990, when he attended the second World Climate Conference in Geneva. His first COP was COP2 in 1996, and then all the COPs between 2010 and 2019. “We are trapped in a bit of a time warp because the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is now 30 years old, and does not fully reflect what we know, what is needed, what technology there is and who is rich and who is poor. When I came back to the COPs after being away for a while there were still some of the same faces and some new ones, but it felt like not much had changed apart from everyone being older. COP17 in Durban sticks in my mind because we were tasked with facilitating a compromise text. We had been talking for 10 days on a particular financial issue, but it took someone from the secretariat to suggest we remove a phrase to start moving things along again. The setting of negotiations is very important. You need to see each others faces and not be too far apart from each other. It used to be about a raised eyebrow or a wink, but technology has changed that. Now people are negotiating using all different channels. It feels like speed dating compared to old fashioned dating.” While I was making the portrait of Stefano, he could hear my voice, but I could not hear his. In the end we had to say goodbye with a wave and namaste hands as we could not re-establish the connection.

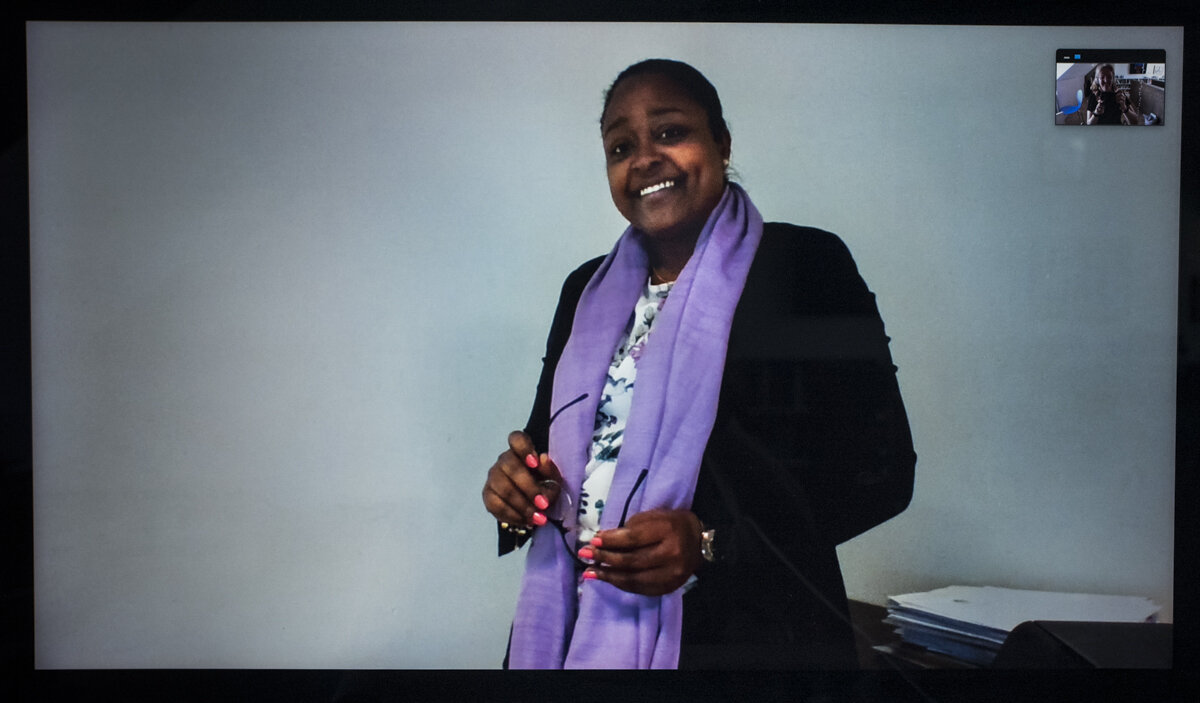

I managed to catch Stella on her way home from a visit to her family. She got out of the car and asked a passerby if they would hold the phone while I took a picture. It was a busy road and it was difficult to hear, so then she got back in the car to talk. Stella has attended every COP since Durban in 2011. She represents Malawi and the LDCs. “Negotiating is hard work. Sometimes it’s frustrating when people do not understand the group position. There are lots of procedures and politics. I opted to work on gender and I was surprised that there was resistance. In Malawi, there is a gender policy and a lot of awareness about the importance of gender parity. Even in the villages, if you go to set up a group, people will always say that it is important to have both men and women involved. So, I thought that the gender agenda would sail through the UNFCCC negotiations and I was not prepared for the challenges. However, we got enough support and now we have the Lima Work Programme on Gender and it has been integrated into the convention. In the end we were successful and that’s what matters.”

Paul has been to every COP since COP6 in the Hague in 2000. He used to lead the French negotiating team but now he is an advisor. “People think they are solving climate change through negotiation but they are not. The negotiation is important, but it is the action that is essential. The Paris Agreement tells us what the goal is, but everything else still needs to be implemented to make it happen. It’s still a huge task. Some recent COPs have had up to 30,000 participants, as there was a lot of knowledge exchange around the negotiations. COPs probably need to get smaller again now. It cannot all be done on-line though. Human contact is a really important part of the discussions. As a negotiator you need to listen to what people really need, not necessarily what they say. You need to find a common ground. If you want to try and stick to your position, you need a really strong argument. Usually, there’s one thing you need to stick to and others that you can be more flexible about. Sometimes it’s easy to find a compromise during informal discussions, but other times there are large differences and the common ground is tougher to find. COPs are not good for your health or your mental health!”

I spoke to Kunzang at her mother’s house in the countryside in Bhutan. Normally she lives in the capital city, Thimphu, but she was spending some time working remotely from the family home. Kunzang first attended negotiations in 2018 but had been advising on agreements for some time, so she knew what to expect. "The developed countries have huge delegations which are well prepared. You really need support when you are negotiating because sometimes negotiations happen on the fly. Although LDCs have a tough task, we are proud of what we achieve and how we coordinate. At my first COP (COP24), I led the Global Stocktake negotiations. The pressure is really energy draining, but when you get something into an agreement, it is really very satisfying. At Glasgow I will be working with the capacity building group for developing countries. The parties have been meeting on-line which has gone well, but we have had to get up at 3am in order to participate. The LDC negotiators have a completely different experience. The human resource constraints are real, but we do our best and I still have energy".

Franz has been a climate negotiator since 2010. He represents Switzerland and also coordinates the Environmental Integrity Group, which comprises Georgia, Liechtentsein, Mexico, Monaco, the Republic of Korea and Switzerland. It’s the only group which is a mix of developed and developing nations. “What people do not realise is that the negotiators are like a family. I’ve been involved in other negotiations and it’s always the same. The climate change negotiations are bigger and longer, but it still applies. There are a group of people who you know really well and you know the dynamics and how they work better with some than others, but it’s just like a family. They are all really nice people and sometimes that really helps to make it easier to find solutions. Each COP has its own special memories and its own drama. People ask me how I remain motivated, but you almost always make some small progress, even though it is not enough, at least you can be proud that you are doing something.”

Sara Zoomed me from an incredible traditional museum setting in Jeddah. She attended COPs between 2012 and 2019 as part of Saudi Arabia’s delegation. She was the first female on that team, but now the majority of Saudi negotiators are women. “Sometimes you are across the table arguing with someone over one issue and then you will be beside them in agreement over something else. You need to have solid interpersonal skills. If you are chairing a group you have to care for all and make sure that even those with just one person delegations, like some of the small island states, get their say and a fair representation. As a negotiator, you have a mandate from your country, but you also have to take different roles when you are a presiding officer and you have to take care of the process. I was very honoured to do this. It’s not just about national interest. It’s about multilateralism. It can be challenging, but you have to understand other view points.”

Juliana attended her first COP in 2014 in Lima, Peru, when she was 25. She now leads the Colombian delegation and coordinates positions on climate ambition for countries from her region. “In Lima, I was a young woman in a very male dominated environment. That is changing, but only slowly. Negotiating is exhausting, both physically and emotionally. There is no time for rest, food and sometimes even water. You are constantly trying to find solutions and you cannot miss anything, so you are working 24/7. I am fortunate that I defend a position that I truly believe in. No matter how big or small our achievements in the negotiations are, we are happy to contribute to the larger cause by trying to do our best and inspiring bigger countries to do more.”

Jacob attended his first climate negotiation in 1991 and for ten years worked with Alliance of Small Island States in the design of the UN Framework Convention and the Kyoto Protocol. At COP26 Jacob will head the delegation of the European Union. Jacob is US born and raised and has UK citizenship. He has moved in and out of the process over the last three decades, and notes its not unusual for colleagues to be drawn back into the negotiations in one role or another. “The process is very intense and people say it is addictive. People continue because they are committed to this issue - that’s certainly true for me - but also because of the friends and relationships that are built up with negotiators from all over the world.”

Marianne has represented Norway at COPs since 2008. She is now chair of the Subsidiary Body for Implementation. “I tend to remember the COPs by the decisions that are made. You also remember the people, the late nights and the food, which if it isn’t very good might be instant soup from home! The Polish are really good at food. I’ve been to three COPs in Poland and they have all had good food. In Doha my average daily walk was about 10km because the conference centre was so big. In Copenhagen there was a time when the adaptation negotiators were forgotten. The ministers had agreed something an hour before, and we were still negotiating, but no-one told us! That wouldn’t happen now. The toilets are like festival toilets! When the celebrities like Greta come, the negotiators are usually busy negotiating. In Copenhagen I remember being so tired that I was asleep on a beanbag and all I heard of Obama was his chopper flying overhead. We also rarely get to see the protestors. When they are protesting, we are negotiating. When we finish, they are partying. When we arrive int he morning, they are sleeping!” I had to photograph Marianne without sound from her. The process involved much hand waving, but in the end we got it together.

Benito is not a climate negotiator, but I have included him here because of all his work supporting negotiators. He has attended about 20 of the 25 COPs to date and he introduced me to many of negotiators who I have photographed. Benito is the managing director of Oxford Climate Policy, an organisation which brings together climate negotiators from developing countries every year in Oxford, to help strengthen their capacity and also to build connections with European negotiators. Benito told me “The negotiations are like a small village which pops up all over the world, with about 5000 inhabitants and about 15000 tourists! There are all the dynamics that you find in a village community. There are alliances and some lack of trust between different groups. Once the relationships are established one way or another, it can take years to change. It's often during the down time at the COPs, that the productive discussions can happen and deals can be found. So I worry that the culture has moved towards working 24 hours a day. Opportunities will be missed.”

Artur’s first COP was in 1998 in Buenos Aires and he has represented the European Union at many COPs since then. He says the most important thing about negotiating is to respect everybody. “Every COP has its own happy memories. You need to be open, to listen and to talk in order to succeed. You also need endurance and patience as you have to hear many things over and over again. A big part of the Paris Agreement is for countries to cooperate and support each other. Different government’s responses to the pandemic has made this more challenging.”

Farrukh’s first COP was in Bali in 2007. He represented Pakistan and was involved in negotiating many climate change instruments. “Understanding the politics and the art of making a deal is central to UNFCCC process. Unfortunately, that process is not keeping up with the changing global climate. Even though the membership has not yet found all the solutions, one silver-lining is that they have agreed on a common platform: the Paris Agreement. A big remaining challenge is to integrate and value the contributions of non-state actors whose decisions have a huge impact on the climate, such as banks, financial markets, pension funds, and asset managers. We need to strengthen links with them, supports their efforts and engage them more. We are working on that.”

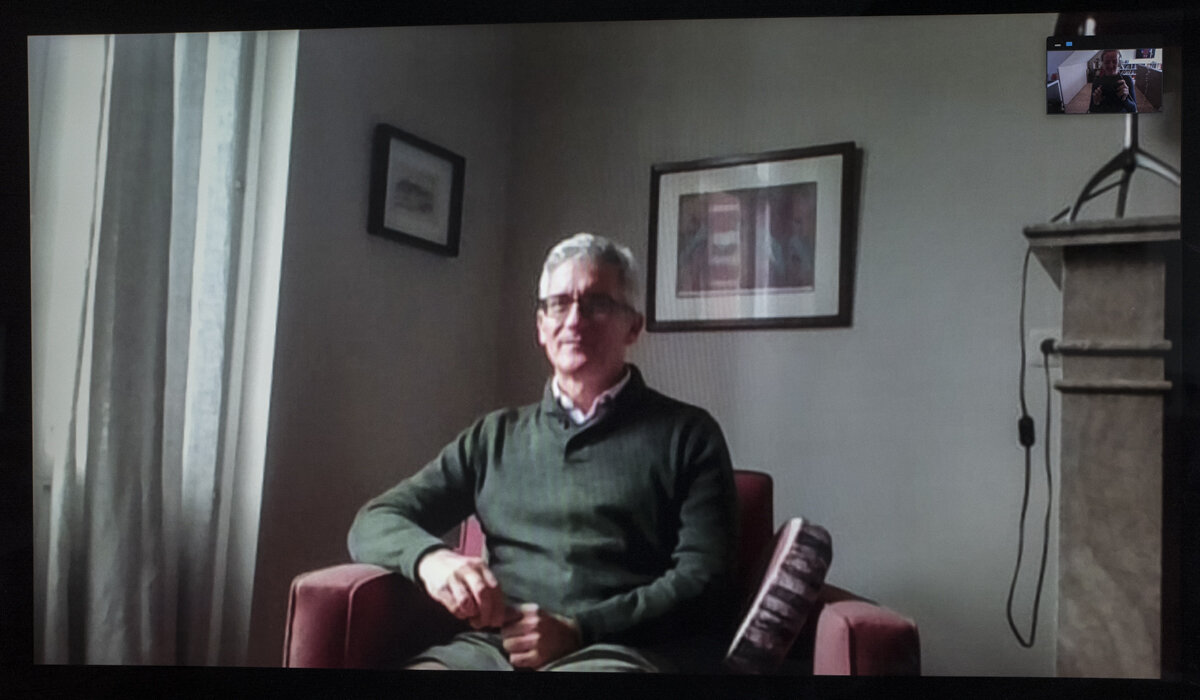

Peter has been involved in the COPs, representing the UK, since 1998 in Buenos Aires. Between 2010 and 2016 he was the lead negotiator for the EU. “The COPs are very complicated and there is not always clarity over who is responsible for the processes. Sometimes entire meetings can be lost because one delegation objects to the agenda. Most of the negotiators know each other, and know what each other thinks. Everyone reads out their national speaking points in the plenary but we need to get into less formal environments to work out how positions might change. It’s messy, it’s adversarial at times, but it’s an incredible act of co-creation. The human desire not to be excluded is very powerful. No-one wants to be the only one to refuse to sign up to something. The real challenge now is for the politicians who need to make difficult decisions on behalf of future generations. “

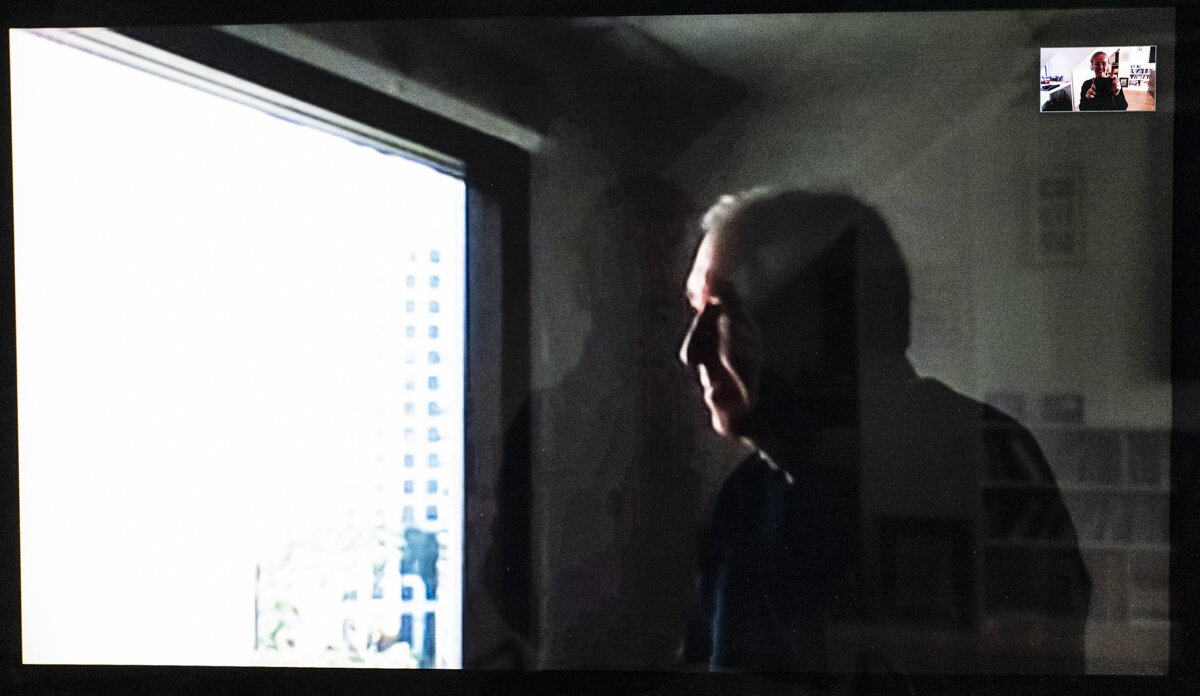

Gylvan is from Brazil and was involved in discussions about climate change since 1990. He was part of the International Negotiating Committee which created the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and then attended every COP since the first one was held in Bonn in 1995. “As negotiators you follow the UN rules. There is no voting and all the decisions have to be made by consensus. If there is a situation where most countries have agreed, but there is one outlier, they say what you need is a chairman with a fast gavel. Either that or you suggest that you will write a footnote which explains that everyone agreed except for country X. Nobody wants to be that country. In reality all the negotiators are professionals and friends with the common objective of resolving climate change. People really want to work together and find an agreement. “ Gylvan’s colleagues tried to help me make this picture, but no-one could hear what I was asking them to do, so there was much good natured yelling and I even tried drawing pictures to explain myself. We all did the best we could, given the circumstances. Next time I need to brush up on my Portuguese.

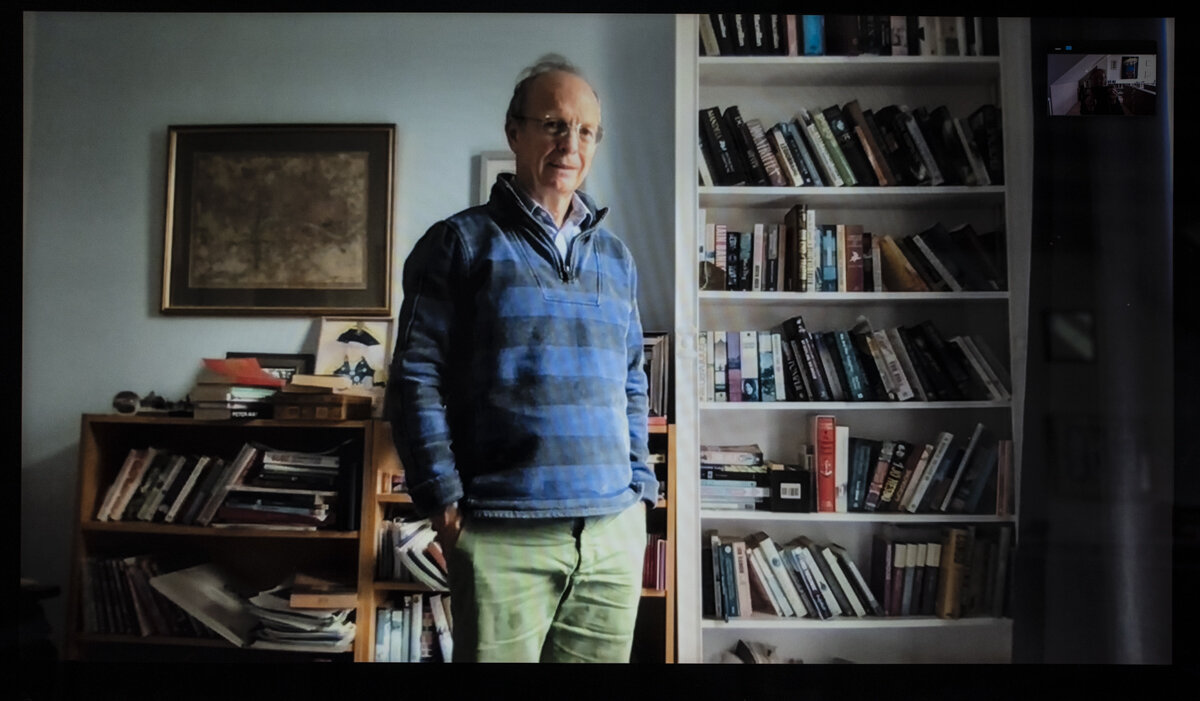

Tomasz represented Poland at the COPS between 2006 and 2018. He says negotiating is fascinating: “You meet 100s if not 1000s of people from around the world. The most important things are to listen and to show respect. If you do not care what others think, then you cannot expect others to respect your position. You must demonstrate an equal willingness to listen as to talk. Over the years, the size of the negotiations has grown, but so has the public acceptance of the need for the process.” As I spoke with Tomasz I noticed him looking out of the window. Tomasz said he especially appreciates having a window because so many negotiations are carried out in windowless conference rooms.

Teresa is the Deputy Prime Minister of Spain and has attended almost all COPs since COP6 bis in Bonn. Teresa hoped to attend COP6 in the Hague but she was having a baby so she could not. The talks in the Hague broke down, and so COP6 bis happened 6 months later, and Teresa could attend. She says: “Over the years we negotiators have become very good friends. It has gone from “How is your baby?” to “How is your child?” to “How is your teenager?” to “How is your young person?” Sometimes people dismiss negotiators as bureaucrats, but the COP negotiators are very committed to the climate agenda. You have to consider others and develop empathy towards others who consider the issues differently. Of course my favourite COP was in Madrid in 2019. We decided to help our friends in Chile by taking over the organisation at late notice, and it was a very powerful message that we would bring it together in just 2 months. We had no idea that it would be the last opportunity to meet in person for such a long time. Sometimes you really need face to face meetings.”

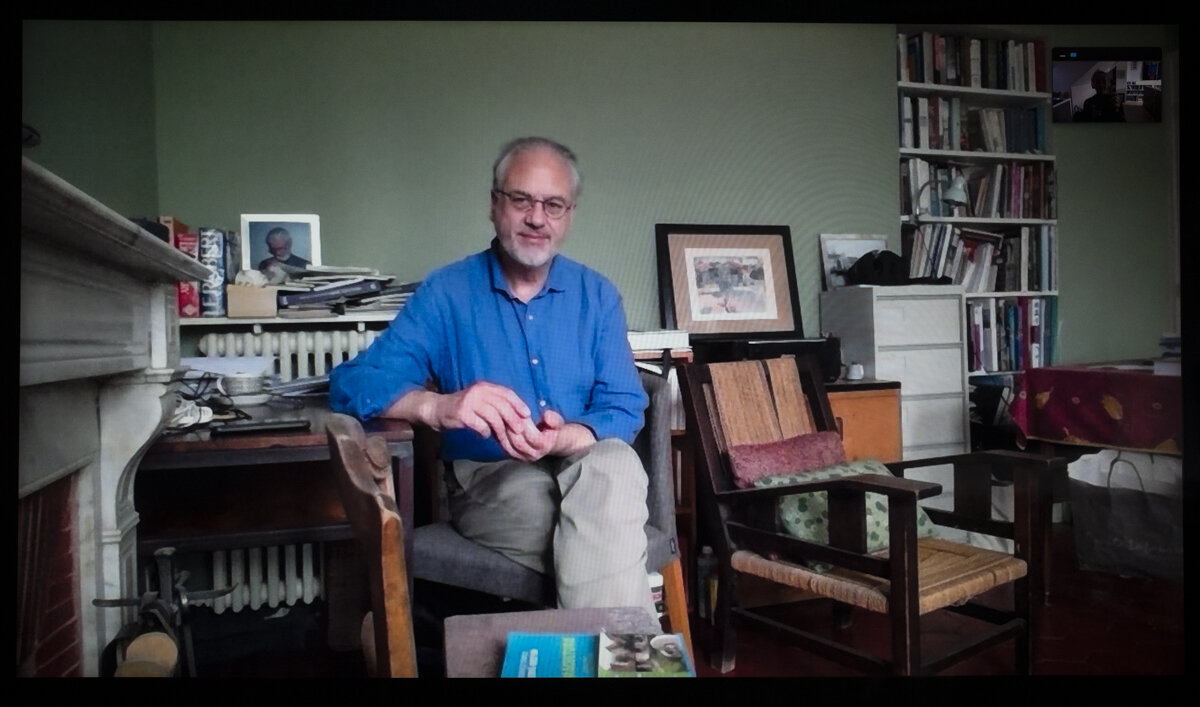

Jos went to his first COP in Japan in 2003, where the Kyoto Protocol was agreed. Jos has negotiated on behalf of Belgium and the EU. He always worked on issues of finance, which he believes were somewhat easier to agree than the technical issues. “There are the formal parts of the negotiations where you state your official position, over the microphone. Then there is the informal part where you meet with smaller groups of people over coffee or in the corridor in order to try and work out a solution. You can be more flexible in this environment. After some years you know many of the people and the conversations are normally very friendly and constructive. Now that we have negotiated the Paris Agreement, the emphasis is on implementation. Politicians and heads of state need to take responsibility. There’s an argument for smaller COPs now. The nature of the meetings will change as they are about reviewing and implementing rather than negotiating.“

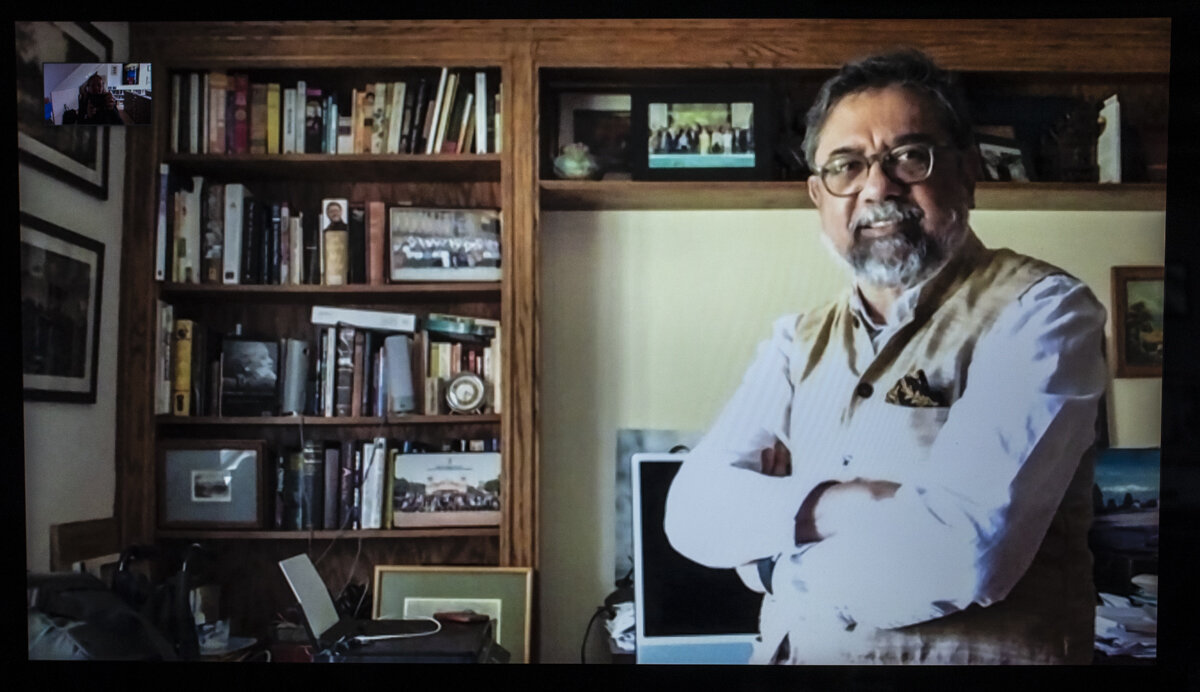

Dipak has been attending COPs since the 2011 meeting in Durban. He worked primarily for the Indian Government negotiating issues related to climate change finance. He was a founding board member of the Green Climate Fund. “There is a lot of wordsmithing in negotiating. Going through every sentence and every line of an agreement. But the important thing is the intent. Smart negotiators are very diplomatic and in fact many of them come from the foreign service. As an economist, my job was to guide thinking on finance. Sometimes the developed countries asked “Why are you being so difficult?”, but I was just trying to represent developing nations, and make sure that what was being promised was delivered. Large developing nations will find a way, but the little ones really need help.”

Cecilia is from Angola and has been attending COPs since COP15 in Copenhagen. She planned to attend COP16 in Cancun but could not because she was pregnant and there were complications. However, she has attended every COP since then. Since 2016 Cecilia has also represented the LDCs (Least Developed Countries) with a particular focus on the adaptation agenda. “I am very interested in adaptation for climate change. I am now the co-chair of the adaptation committee. Many women in developing countries are responsible for the adaptation projects in their countries but a woman has never been chair of the LDC group. I hope to do that job in the future. I really want to make a difference.” I had to make Cecilia’s portrait using her desktop because her laptop did not have wifi in her office. It limited our options but we did our best.

I photographed Annela as thunder raged around her house in Estonia. At one point the storm even cut us off completely. Annela’s first COP was in 2009, where she attended as part of the Estonian government delegation. This year she is the EU’s lead negotiator in Response Measures. “We always negotiate the actual draft decision texts in English, whether formally or informally. But the language negotiators use is very specific and certain words hold a lot more weight than they might otherwise in normal use. We do not record the negotiations outside plenaries, and we do not name specific parties and don’t attribute what they say. When I am negotiating I like to have my team next to me and behind me. So that they have my back. It’s really difficult to negotiate alone in front of my laptop. We use WhatsApp with our team, but it’s not the same. The different time zones also makes international negotiations on-line difficult. At the in-person meetings, we may have jet lag, but at least we are all in the same time zone. It’s really important to have long term negotiators because they remind us what has already been thrashed out in the past. I am trying to get off-ground a network of senior women negotiators. It is important to have this kind of support system for women. They are sometimes reluctant to take leading roles because of their other responsibilities. Mirtel my cat, has been supporting me during recent negotiations - sleeping behind my computer screen during early morning negotiations.”

Manjeev represented India at the COP negotiations between 2005 and 2009. “My first meeting was in Montreal and it was extremely cold outside. Not something I had been used to. It was a steep learning curve when I first became involved in the negotiations. I’d been in the foreign service before but I entered as a mid-level negotiator. At the time the US were very concerned about the developing countries not having to do enough. We wanted to developed countries to lead, while we did what we could. In Bali it was similar, the US were putting pressure on India to take more responsibility, but the Indians wanted differentiated responsibility. At that time it was still difficult to communicate with minister back home. We didn’t have smart phones and so sometimes by the time you had connected with your people the discussions had already moved on. The interesting thing about the UN methodology is that there has to be consensus. These COPs were the most defining negotiations of a generation. Of all the things we negotiate, climate change is the one where international cooperation is essential. The negotiations were among the most exhilarating things I have been involved in both intellectually and in terms of what I stand for. Everyone has a personal stake in it.”

After three video meetings to make this portrait with Bo Kjellen, veteran climate negotiator, I can testify that he does not give up easily. We battled with limited bandwidth, computing power and a broken webcam until finally Bo’s face appeared before me. I was so delighted to make a brief connection that I can only look at this image and smile. I am sure this tenacity is why Bo was such a successful negotiator. He was involved in climate discussions from the early 1990s. Bo was Sweden’s chief negotiator at COP1, where he led international negotiations along with some promising colleagues: “The discussions were difficult but eventually we agreed the Berlin Protocol. The German environment minister, Angela Merkel, was very helpful.” At the decisive COP3, Bo was instrumental in finding agreement between the EU, the US and the Group of 77 developing countries. Their wording was accepted at the final hour and contributed to the landmark Kyoto Protocol that is still in place today. When George W Bush entered the White House and threatened to derail the negotiations, it was Bo and his Swedish colleagues, in the capacity of the EU presidency, who convinced the Americans to remain passive. Bo will follow COP26 from his home in Uppsala: “I’m sure the Brits will make the best out of Glasgow. It’s possible that after recent events there will be support for something big.”

Frode has attended 8 COPs since 2002. He will attend COP26 and is primarily working on the adaptation agenda, helping more vulnerable nations to cope with the challenges that climate change brings. “Cities like Paris, Kyoto, Bali, Copenhagen, are no longer just a place on a map to me. Their names have taken on a much greater meaning as landmarks in the climate change journey. Over that time, other negotiators have become like family. You get to know each other so well during the intense, around the clock, meetings. The relationships are very special. In addition, the world has changed so much since the negotiations started. Back then we had a simplistic distinction between rich and poor countries. Now the world is much more diverse and the differences are much more nuanced. Some countries find it hard to move their negotiating position on, even though their economies have become much stronger. ”

Marco has been passionate about climate change since the early 1980s when, as a teenager, he used to insist on walking everywhere to avoid emissions and as a kind of protest. His first COP was in 2003 in Milan and he has been to several COPs since then, including Madrid in 2019. “Negotiating on climate is a mixture of passion and patience. The UN machinery is huge, and on top of that there are all the sovereign member states, but there is no alternative but to try and bring everyone along through negotiation. Right now I feel hopeful because key players like the EU, China, Brazil and the US are committed to ambitious goals, notably climate neutrality by 2050 or 2060. A lot needs to be done before we get there, but this level of ambition unprecedented”

Stefano is from Switzerland and has been involved in climate negotiations since 1990, when he attended the second World Climate Conference in Geneva. His first COP was COP2 in 1996, and then all the COPs between 2010 and 2019. “We are trapped in a bit of a time warp because the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is now 30 years old, and does not fully reflect what we know, what is needed, what technology there is and who is rich and who is poor. When I came back to the COPs after being away for a while there were still some of the same faces and some new ones, but it felt like not much had changed apart from everyone being older. COP17 in Durban sticks in my mind because we were tasked with facilitating a compromise text. We had been talking for 10 days on a particular financial issue, but it took someone from the secretariat to suggest we remove a phrase to start moving things along again. The setting of negotiations is very important. You need to see each others faces and not be too far apart from each other. It used to be about a raised eyebrow or a wink, but technology has changed that. Now people are negotiating using all different channels. It feels like speed dating compared to old fashioned dating.” While I was making the portrait of Stefano, he could hear my voice, but I could not hear his. In the end we had to say goodbye with a wave and namaste hands as we could not re-establish the connection.

I managed to catch Stella on her way home from a visit to her family. She got out of the car and asked a passerby if they would hold the phone while I took a picture. It was a busy road and it was difficult to hear, so then she got back in the car to talk. Stella has attended every COP since Durban in 2011. She represents Malawi and the LDCs. “Negotiating is hard work. Sometimes it’s frustrating when people do not understand the group position. There are lots of procedures and politics. I opted to work on gender and I was surprised that there was resistance. In Malawi, there is a gender policy and a lot of awareness about the importance of gender parity. Even in the villages, if you go to set up a group, people will always say that it is important to have both men and women involved. So, I thought that the gender agenda would sail through the UNFCCC negotiations and I was not prepared for the challenges. However, we got enough support and now we have the Lima Work Programme on Gender and it has been integrated into the convention. In the end we were successful and that’s what matters.”

Paul has been to every COP since COP6 in the Hague in 2000. He used to lead the French negotiating team but now he is an advisor. “People think they are solving climate change through negotiation but they are not. The negotiation is important, but it is the action that is essential. The Paris Agreement tells us what the goal is, but everything else still needs to be implemented to make it happen. It’s still a huge task. Some recent COPs have had up to 30,000 participants, as there was a lot of knowledge exchange around the negotiations. COPs probably need to get smaller again now. It cannot all be done on-line though. Human contact is a really important part of the discussions. As a negotiator you need to listen to what people really need, not necessarily what they say. You need to find a common ground. If you want to try and stick to your position, you need a really strong argument. Usually, there’s one thing you need to stick to and others that you can be more flexible about. Sometimes it’s easy to find a compromise during informal discussions, but other times there are large differences and the common ground is tougher to find. COPs are not good for your health or your mental health!”

I spoke to Kunzang at her mother’s house in the countryside in Bhutan. Normally she lives in the capital city, Thimphu, but she was spending some time working remotely from the family home. Kunzang first attended negotiations in 2018 but had been advising on agreements for some time, so she knew what to expect. "The developed countries have huge delegations which are well prepared. You really need support when you are negotiating because sometimes negotiations happen on the fly. Although LDCs have a tough task, we are proud of what we achieve and how we coordinate. At my first COP (COP24), I led the Global Stocktake negotiations. The pressure is really energy draining, but when you get something into an agreement, it is really very satisfying. At Glasgow I will be working with the capacity building group for developing countries. The parties have been meeting on-line which has gone well, but we have had to get up at 3am in order to participate. The LDC negotiators have a completely different experience. The human resource constraints are real, but we do our best and I still have energy".

Franz has been a climate negotiator since 2010. He represents Switzerland and also coordinates the Environmental Integrity Group, which comprises Georgia, Liechtentsein, Mexico, Monaco, the Republic of Korea and Switzerland. It’s the only group which is a mix of developed and developing nations. “What people do not realise is that the negotiators are like a family. I’ve been involved in other negotiations and it’s always the same. The climate change negotiations are bigger and longer, but it still applies. There are a group of people who you know really well and you know the dynamics and how they work better with some than others, but it’s just like a family. They are all really nice people and sometimes that really helps to make it easier to find solutions. Each COP has its own special memories and its own drama. People ask me how I remain motivated, but you almost always make some small progress, even though it is not enough, at least you can be proud that you are doing something.”

Sara Zoomed me from an incredible traditional museum setting in Jeddah. She attended COPs between 2012 and 2019 as part of Saudi Arabia’s delegation. She was the first female on that team, but now the majority of Saudi negotiators are women. “Sometimes you are across the table arguing with someone over one issue and then you will be beside them in agreement over something else. You need to have solid interpersonal skills. If you are chairing a group you have to care for all and make sure that even those with just one person delegations, like some of the small island states, get their say and a fair representation. As a negotiator, you have a mandate from your country, but you also have to take different roles when you are a presiding officer and you have to take care of the process. I was very honoured to do this. It’s not just about national interest. It’s about multilateralism. It can be challenging, but you have to understand other view points.”

Juliana attended her first COP in 2014 in Lima, Peru, when she was 25. She now leads the Colombian delegation and coordinates positions on climate ambition for countries from her region. “In Lima, I was a young woman in a very male dominated environment. That is changing, but only slowly. Negotiating is exhausting, both physically and emotionally. There is no time for rest, food and sometimes even water. You are constantly trying to find solutions and you cannot miss anything, so you are working 24/7. I am fortunate that I defend a position that I truly believe in. No matter how big or small our achievements in the negotiations are, we are happy to contribute to the larger cause by trying to do our best and inspiring bigger countries to do more.”

Jacob attended his first climate negotiation in 1991 and for ten years worked with Alliance of Small Island States in the design of the UN Framework Convention and the Kyoto Protocol. At COP26 Jacob will head the delegation of the European Union. Jacob is US born and raised and has UK citizenship. He has moved in and out of the process over the last three decades, and notes its not unusual for colleagues to be drawn back into the negotiations in one role or another. “The process is very intense and people say it is addictive. People continue because they are committed to this issue - that’s certainly true for me - but also because of the friends and relationships that are built up with negotiators from all over the world.”

Marianne has represented Norway at COPs since 2008. She is now chair of the Subsidiary Body for Implementation. “I tend to remember the COPs by the decisions that are made. You also remember the people, the late nights and the food, which if it isn’t very good might be instant soup from home! The Polish are really good at food. I’ve been to three COPs in Poland and they have all had good food. In Doha my average daily walk was about 10km because the conference centre was so big. In Copenhagen there was a time when the adaptation negotiators were forgotten. The ministers had agreed something an hour before, and we were still negotiating, but no-one told us! That wouldn’t happen now. The toilets are like festival toilets! When the celebrities like Greta come, the negotiators are usually busy negotiating. In Copenhagen I remember being so tired that I was asleep on a beanbag and all I heard of Obama was his chopper flying overhead. We also rarely get to see the protestors. When they are protesting, we are negotiating. When we finish, they are partying. When we arrive int he morning, they are sleeping!” I had to photograph Marianne without sound from her. The process involved much hand waving, but in the end we got it together.

Benito is not a climate negotiator, but I have included him here because of all his work supporting negotiators. He has attended about 20 of the 25 COPs to date and he introduced me to many of negotiators who I have photographed. Benito is the managing director of Oxford Climate Policy, an organisation which brings together climate negotiators from developing countries every year in Oxford, to help strengthen their capacity and also to build connections with European negotiators. Benito told me “The negotiations are like a small village which pops up all over the world, with about 5000 inhabitants and about 15000 tourists! There are all the dynamics that you find in a village community. There are alliances and some lack of trust between different groups. Once the relationships are established one way or another, it can take years to change. It's often during the down time at the COPs, that the productive discussions can happen and deals can be found. So I worry that the culture has moved towards working 24 hours a day. Opportunities will be missed.”

Artur’s first COP was in 1998 in Buenos Aires and he has represented the European Union at many COPs since then. He says the most important thing about negotiating is to respect everybody. “Every COP has its own happy memories. You need to be open, to listen and to talk in order to succeed. You also need endurance and patience as you have to hear many things over and over again. A big part of the Paris Agreement is for countries to cooperate and support each other. Different government’s responses to the pandemic has made this more challenging.”

Farrukh’s first COP was in Bali in 2007. He represented Pakistan and was involved in negotiating many climate change instruments. “Understanding the politics and the art of making a deal is central to UNFCCC process. Unfortunately, that process is not keeping up with the changing global climate. Even though the membership has not yet found all the solutions, one silver-lining is that they have agreed on a common platform: the Paris Agreement. A big remaining challenge is to integrate and value the contributions of non-state actors whose decisions have a huge impact on the climate, such as banks, financial markets, pension funds, and asset managers. We need to strengthen links with them, supports their efforts and engage them more. We are working on that.”

Peter has been involved in the COPs, representing the UK, since 1998 in Buenos Aires. Between 2010 and 2016 he was the lead negotiator for the EU. “The COPs are very complicated and there is not always clarity over who is responsible for the processes. Sometimes entire meetings can be lost because one delegation objects to the agenda. Most of the negotiators know each other, and know what each other thinks. Everyone reads out their national speaking points in the plenary but we need to get into less formal environments to work out how positions might change. It’s messy, it’s adversarial at times, but it’s an incredible act of co-creation. The human desire not to be excluded is very powerful. No-one wants to be the only one to refuse to sign up to something. The real challenge now is for the politicians who need to make difficult decisions on behalf of future generations. “

Gylvan is from Brazil and was involved in discussions about climate change since 1990. He was part of the International Negotiating Committee which created the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and then attended every COP since the first one was held in Bonn in 1995. “As negotiators you follow the UN rules. There is no voting and all the decisions have to be made by consensus. If there is a situation where most countries have agreed, but there is one outlier, they say what you need is a chairman with a fast gavel. Either that or you suggest that you will write a footnote which explains that everyone agreed except for country X. Nobody wants to be that country. In reality all the negotiators are professionals and friends with the common objective of resolving climate change. People really want to work together and find an agreement. “ Gylvan’s colleagues tried to help me make this picture, but no-one could hear what I was asking them to do, so there was much good natured yelling and I even tried drawing pictures to explain myself. We all did the best we could, given the circumstances. Next time I need to brush up on my Portuguese.

Tomasz represented Poland at the COPS between 2006 and 2018. He says negotiating is fascinating: “You meet 100s if not 1000s of people from around the world. The most important things are to listen and to show respect. If you do not care what others think, then you cannot expect others to respect your position. You must demonstrate an equal willingness to listen as to talk. Over the years, the size of the negotiations has grown, but so has the public acceptance of the need for the process.” As I spoke with Tomasz I noticed him looking out of the window. Tomasz said he especially appreciates having a window because so many negotiations are carried out in windowless conference rooms.

Teresa is the Deputy Prime Minister of Spain and has attended almost all COPs since COP6 bis in Bonn. Teresa hoped to attend COP6 in the Hague but she was having a baby so she could not. The talks in the Hague broke down, and so COP6 bis happened 6 months later, and Teresa could attend. She says: “Over the years we negotiators have become very good friends. It has gone from “How is your baby?” to “How is your child?” to “How is your teenager?” to “How is your young person?” Sometimes people dismiss negotiators as bureaucrats, but the COP negotiators are very committed to the climate agenda. You have to consider others and develop empathy towards others who consider the issues differently. Of course my favourite COP was in Madrid in 2019. We decided to help our friends in Chile by taking over the organisation at late notice, and it was a very powerful message that we would bring it together in just 2 months. We had no idea that it would be the last opportunity to meet in person for such a long time. Sometimes you really need face to face meetings.”

Jos went to his first COP in Japan in 2003, where the Kyoto Protocol was agreed. Jos has negotiated on behalf of Belgium and the EU. He always worked on issues of finance, which he believes were somewhat easier to agree than the technical issues. “There are the formal parts of the negotiations where you state your official position, over the microphone. Then there is the informal part where you meet with smaller groups of people over coffee or in the corridor in order to try and work out a solution. You can be more flexible in this environment. After some years you know many of the people and the conversations are normally very friendly and constructive. Now that we have negotiated the Paris Agreement, the emphasis is on implementation. Politicians and heads of state need to take responsibility. There’s an argument for smaller COPs now. The nature of the meetings will change as they are about reviewing and implementing rather than negotiating.“

Dipak has been attending COPs since the 2011 meeting in Durban. He worked primarily for the Indian Government negotiating issues related to climate change finance. He was a founding board member of the Green Climate Fund. “There is a lot of wordsmithing in negotiating. Going through every sentence and every line of an agreement. But the important thing is the intent. Smart negotiators are very diplomatic and in fact many of them come from the foreign service. As an economist, my job was to guide thinking on finance. Sometimes the developed countries asked “Why are you being so difficult?”, but I was just trying to represent developing nations, and make sure that what was being promised was delivered. Large developing nations will find a way, but the little ones really need help.”

Cecilia is from Angola and has been attending COPs since COP15 in Copenhagen. She planned to attend COP16 in Cancun but could not because she was pregnant and there were complications. However, she has attended every COP since then. Since 2016 Cecilia has also represented the LDCs (Least Developed Countries) with a particular focus on the adaptation agenda. “I am very interested in adaptation for climate change. I am now the co-chair of the adaptation committee. Many women in developing countries are responsible for the adaptation projects in their countries but a woman has never been chair of the LDC group. I hope to do that job in the future. I really want to make a difference.” I had to make Cecilia’s portrait using her desktop because her laptop did not have wifi in her office. It limited our options but we did our best.